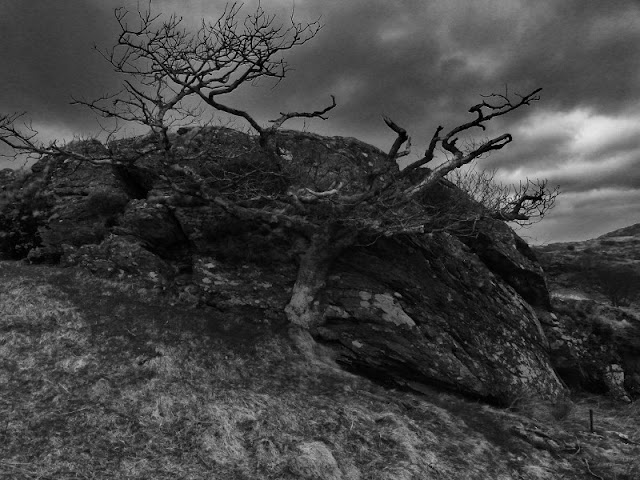

The climb up to Rhosydd is quite a thought, especially on a dull, misty morning. But experience tells us that the place has always been worth the effort. Even in the rain, there's something magical about this mine, nestling high on a shoulder of the mighty Moelwyn Mawr. Oh, and this time we intended to capture some shots inside the fabled 9 adit.

9 adit is a long one- at 2,221 feet it's just under half a mile, straight into the hillside. It took eight years to drive, at a gradient of 1:86; like all adits, it is arranged so that water will drain out of the mine. Completed some time between 1870 or 1871, at the same time as a big incline was also being tunnelled from floor 5 down to floor 9. (At Rhosydd, the floors are numbered downwards- one, being the highest, to 14 being the lowest.)

I can only imagine the logistics of an operation like this, all done by surveyors measuring without 3D imaging or laser technology. When the miners driving 9 adit met the miners driving the incline tunnel, it is said that a large crowd had gathered underground to witness the breakthrough. As the rock between was blasted away, the crowd "fell like dominoes from the blast" There is no record of whether anyone was hurt..

Of course, the adit is wet, but nothing that would trouble a pair of wellingtons. We sploshed along for what seemed like ages until we came to a crosscut, where a chamber opened out. It was an attempt to work the Blaenau North Vein, reminiscent of Conglog, just a mile or so down to the North West. But the main workings were still a good many footsteps down the tunnel yet.

![]() |

| The Compressor Alcove |

After more sploshing, an alcove opened up on the right. It was, according to Lewis and Denton*, a compressor room, where in 1921 a machine was installed by Broom & Wade to provide air for drills working the then newly opened back vein workings. The compressor itself was driven by water, from a reservoir higher up the hill above at Cwmcorsiog. Much use was made of water power within the mine, and occasionally we could see the remains of the 6" main pipes that had transported it- although most had fallen victim to the scrap man, even at this inaccessible spot.

![]() |

| The Crosscut gallery |

Shortly after the compressor room another crosscut came into view, leading to three large chambers. They are very difficult to light and my photographs didn't do them justice. Petra was far too busy taking her own photographs to become a model for scale, so they went unrecorded by my camera - you'll just have to take my word for it that they were very fine!

![]() |

| First view of Piccadilly Circus |

Finally, we reached the large, low chamber known as "Piccadilly Circus", the transport hub of the mine. Here an incline went up to floor 5 and another down to floor 14. Level 9 was where all the traffic for the mine was marshalled and sent out to the mill, using a continuous haulage system. It was laid as three rails, branching out into double-track at a passing place halfway down the adit.

We found the base of the 5-9 incline where an ingenious system had been in use. A large trolley car (called a

Trwnc) was fitted to take a number of waggons and rolled up and down the incline on large wheels at a gauge of 4'8.5". It was counterbalanced by a truck which ingeniously passed underneath the cradle, called the

Mochyn, ("pig" in English). This ran on rails at a narrower gauge of 2' 8". It must have been a curious sight as the little

mochyn scuttled underneath the

Trwnc! But the Heath Robinson theme didn't end there, as there was a further twist... where the Trwnc came to rest at the bottom of the incline bisected the entrance to a crosscut from the chambers of 9W. Some way had to be found of crossing...difficult, as this was all on the level. So the quarry engineer dreamed up a moving bridge on wheels, which slid out of the way while the

Trwnc was at the foot of the incline. This ran on 6'5" gauge track. Only the wheels survive and can be seen in the photo. How I would have loved to have seen this in action!

I am being a little uncharitable using the term "Heath Robinson" when all the inclines and their machinery and the equally clever system of water power in the mine were designed by Griffith Griffiths. He seems like the sort of man who would have been comfortable discussing engineering with Brunel and Stephenson, yet was "only" the Rhosydd fitter and carpenter. An indispensable gentleman, I would imagine...I hope he was well paid.

![]() |

Oxford Circus. The counterbalance incline for 9-14 rises in the background.

|

![]() |

| The head of incline 9-14, now flooded all the way down to floor 14. |

An area slightly East of Piccadilly Circus, known as "Oxford Circus" contains The Drumhouse for the 9-14 incline as well as considerable machinery remains, from the various water powered and compressed air plants. The concrete plinths and thousands of holding down bolts tell their own story. The incline disappears down a flooded slope, 463 feet to the base of floor 14. Another incline rises up behind the drumhouse, and this confused us for a while. Then I read that this could have been a counterbalance for the 9-14 incline, which makes sense. Why would two inclines going up be needed otherwise?

![]() |

| Engine Room B9E |

![]() |

The chamber A/B9E engine room, with evidence of a fall behind.

|

After wondering at the scene, we headed east through several chambers. In two, there had been more machinery installed. The level of noise and fumes here can only be imagined as gas engines, Pelton Wheels and compressors all roared away. At various times, Hot Bulb engines and Oil Engines were installed as well as electricity generating units. Our friend Mr Griffiths must have been a very busy man. Behind one of the engine rooms, a massive fall had occurred, blocks the size of a car having fallen in a mighty jumble.

![]() |

| Pointwork, looking towards Oxford Circus |

The trackwork was also of a very high standard in the mine, with pointwork made by the Ffestiniog Railway at Boston Lodge. Because of the three-rail tramway out of the mine, the double flanged wheels so common in other mines locally were entirely absent from Rhosydd, and one or two wheels were lying around underground to prove the point. I wondered if the point frogs were cast at Britannia foundry, but could see no marks. The rail is mostly T rail, 20lbs per yard. One or two chairs still remained, and I was glad they hadn't been taken by souvenir hunters.

![]() |

| Looking towards daylight from the 9 adit sheave winder. |

The mine is a fascinating place and we still have much to explore underground. It's popular with gung-ho explorers for the through trip that can be made from Croesor, something of a rite of passage among the mine exploring fraternity. Which is great if abseiling and underground dinghy sailing is your thing. The downside of it being a popular mine is the litter. We even found some discarded batteries in the water near Piccadilly Circus. Maybe I am being too fussy, perhaps it doesn't matter to most folk, but it spoils the magic a little for me.

I don't want to end this post on a sour note, so I will just say that Rhosydd is rightly one of my favourite locations...the mine and it's setting are spectacular while underground it is evocative and interesting (as well as having some of the most worryingly dodgy ceilings I have seen!) Coming back down the track to Cwmorthin is character building, especially if you have knees like mine that have been damaged by a lifetime of adventuring. But it's all worth it.

*The best authority on the mine is the long out of print Lewis and Denton tome, "Rhosydd Slate Quarry". Copies sometimes come up on Ebay or from specialist booksellers.

![]() |

| At the foot of the 5-9 incline. |

![]() |

| Looking up to floor 6 from the base of the 9-14 counterbalance incline. |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

+(2).jpg)

+(2).jpg)

.jpg)

+(2).jpg)

.jpg)

+(2).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

+(600x800).jpg)

+(800x600).jpg)

+(600x800).jpg)

+(800x586).jpg)

+(800x521).jpg)

+(2).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)